The last issue of the Saturday Evening Post, published on February 8, 1969…

Welcome back to the “Georgia Wasp…”

We were remembering the last decades of the 20 century, as memorialized by and through John Updike’s series of five “Rabbit” novels. (Or four novels and a novella…)

I’d noted that Janice Angstrom – by now Harry’s widow – ended up married to Ronnie Harrison in Rabbit Remembered, the last of the series. (Thelma Harrison – Ronnie’s wife – had also died, and was one of the women with whom Harry had “an affair.”) And not to put too fine a point on it, Harry and Ronnie had known – and hated – each other since high school, when they were teammates on the basketball squad. (They also “shared” Ruth Byers, at different times.)

So now that your up to speed – he wrote sarcastically – let’s get back to the Rabbit is Rich time frame. In mid-winter 1979 the Angstroms jet off to Jamaica, where they end up in an initial wife swap with two other couples. (That’s when Harry first learns that Ronnie’s wife Thelma has the hots for him.) But then they have to go back home before the second swap, where Harry would have “known” the wife he really wanted (Cindy Murkett). Son Nelson is causing no end of problems at the dealership, including smashing up two trade-in convertibles.

The next sequel, Rabbit at Rest, starts with Harry and Janice spending the winter of 1988-89 at their condo in Florida. They leave Nelson in charge of the dealership, which turns out to be a mistake. (He’s hooked on cocaine, which leads Toyota to “pull out,” Freudian slip intended.)

Other incidents include Harry having a heart attack – based on his crappy diet – and having a one-night stand with Nelson’s wife Pru while he recuperates. (Not to mention brief appearances by Annabelle, Harry’s daughter, who’s become a nurse’s aide.)

“Janice’s anger over this betrayal prompts Harry to escape to Florida.” (Wikipedia.) Which leads to one inescapable conclusion: Harry was a bit of a sleazeball, albeit loveable to some.

And finally came Rabbit Remembered, set in late 1999. (On the eve of the New Millennium noted above. ) Harry has died – of another heart attack – while living alone in the Florida condo he “ran” to at the end of Rabbit at Rest. Nelson is still living with his mother, and her new husband Ronnie Harrison, Harry’s old nemesis ever since high school. Nelson’s wife Pru has taken their two children Judy and Roy back to Akron Ohio. Then Annabelle shows up at Janice’s door; her mother Ruth has just died as well.

And finally came Rabbit Remembered, set in late 1999. (On the eve of the New Millennium noted above. ) Harry has died – of another heart attack – while living alone in the Florida condo he “ran” to at the end of Rabbit at Rest. Nelson is still living with his mother, and her new husband Ronnie Harrison, Harry’s old nemesis ever since high school. Nelson’s wife Pru has taken their two children Judy and Roy back to Akron Ohio. Then Annabelle shows up at Janice’s door; her mother Ruth has just died as well.

Aside from Ronnie calling Annabelle “the bastard child of a whore and a bum” at Thanksgiving, the saga includes a tale of childhood sexual abuse, and one of Nelson’s clients committing suicide. (After his bout with cocaine, Nelson became a certified mental-health counselor, thanks in part to a course of study at the “Hubert F. Farnsworth Community College.” Farnsworth was the surname of the same “Skeeter” who’d lived with Harry, Nelson and Jill in the summer of 1969. Skeeter later died in shootout with Philadelphia police.)

To cut to the chase, the final book ends with an uncharacteristic – for Updike – note of hope.

In the rush to make the Y2K celebration, Nelson drives recklessly through an intersection – the stoplights have all gone out – and faces death in the form of a “cocky brat in a baseball cap.” The cocky brat drives an SUV and goes out of turn at a four-way stop. Nelson – with decades of “wrongs, hurts, unjust deaths press[ing] behind his eyes” – faces death and comes out unscathed. (As Winston Churchill – seen at right – said, “There is nothing more exhilarating than to be shot at with no result.“) This act of bravery magically rekindles Pru’s love; “Oh honey, that was great…” Then too, riding in the back seat are Annabelle and Nelson’s childhood friend – and part-time nemesis – Billy Fosnacht. In the end these lost souls start “seeing each other.”

In the rush to make the Y2K celebration, Nelson drives recklessly through an intersection – the stoplights have all gone out – and faces death in the form of a “cocky brat in a baseball cap.” The cocky brat drives an SUV and goes out of turn at a four-way stop. Nelson – with decades of “wrongs, hurts, unjust deaths press[ing] behind his eyes” – faces death and comes out unscathed. (As Winston Churchill – seen at right – said, “There is nothing more exhilarating than to be shot at with no result.“) This act of bravery magically rekindles Pru’s love; “Oh honey, that was great…” Then too, riding in the back seat are Annabelle and Nelson’s childhood friend – and part-time nemesis – Billy Fosnacht. In the end these lost souls start “seeing each other.”

As noted, this happy ending was uncharacteristic of Updike, but aside from that the last novella was enjoyable. And as was characteristic of Updike’s writing, the detail is so thick that I found myself skipping much of it to get to the action. As Charles Portis might say, Updike’s writing lulls you into a sense of woolgathering, and then he socks it to you with an unexpected twist. The result was that I went through Rabbit Remembered the first time quickly, from a sense of impatience more than anything. But now I’ve gone back and started re-reading it, to get the full flavor of the aforementioned Updike attention to detail.

More than that, I pulled out my worn and battered copy of Rabbit Redux, now some 40 years old itself. (I bought the 1971 “Alfred A. Knopf” edition four or five years after it was first published.) And re-reading Rabbit Redux brought back some points I’d forgotten.

For example, on page 9 there’s a bit of foreshadowing, one of Updike’s lesser-known fortes.

It’s the summer of 1969. Harry and his father Earl have gotten off work “from the little printing plant at four sharp.” They have a drink at a neighborhood bar, before taking separate buses home, in opposite directions. Earl asks his son to visit “some evening before the weekend.” (Mary Angstrom “has had Parkinson’s Disease for years now.”) Harry responds:

It’s the summer of 1969. Harry and his father Earl have gotten off work “from the little printing plant at four sharp.” They have a drink at a neighborhood bar, before taking separate buses home, in opposite directions. Earl asks his son to visit “some evening before the weekend.” (Mary Angstrom “has had Parkinson’s Disease for years now.”) Harry responds:

“I don’t like to leave the kid alone in the house. In fact I better be getting back there now just in case.” In case it’s burned down. In case a madman has moved in.

Which is of course just what happens later in the book. A madman – in the form of “Skeeter,” later identified by the Brewer Vat as Hubert Farnsworth – does in fact move in with Harry. He does so at the invitation of Jill, a runaway from Connecticut. She in turn dies in the fire set by neighbors repelled by the “goings on” in the house, after Janice had moved in with Charlie…

But a more personal tidbit comes a bit later, when father and son are settling the bar bill. Earl Angstrom had a Schlitz beer, and tells his son, “Here’s my forty cents. Plus a dime for a tip.”

“Are you kidding me?”

Which is being interpreted: “Do you mean to say there once was a time when you could go into a bar, pay 40 cents for a beer and leave a dime for the tip? And not get thrown out or insulted?”

The answer? Rabbit Redux reminds us that, “Yes, Virginia, there was such a time.”

But the really interesting tidbit – so far – turns on Harry’s mother turning 65. Updike wrote of Earl Angstrom that he “looks merely old” once outside the bar, “liverish scoops below his eyes, broken veins along the sides of his nose.” When Harry asks about their finances Earl responds, “Believe it or not there’s some advantages to living so long in this day and age. This Sunday she’s going to be sixty-five and come under Medicare.”

On Sunday Harry goes to the house with Nelson. (Janice is at Charlie’s.) His mother greets him:

“I’m sixty-five,” she says, groping for phrases, so that her sentences end in the middle. “When I was twenty. I told my boyfriend I wanted to be shot. When I was thirty…” “You told Pop this?” “Not your dad. Another. I didn’t meet your dad til later. This other one, I’m glad. He’s not here to see me now.”

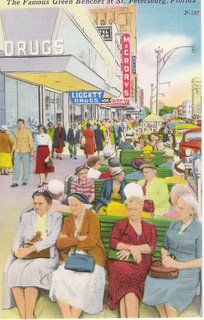

So notwithstanding the fact that Mary has Parkinson’s, Updike’s overall image of 65-year-olds in 1969 is of people who really are over the hill. (“Living so long in this day and age?” Really?) Or as they used to say of St. Petersburg, they were in “God’s Waiting Room” (shown at left):

So notwithstanding the fact that Mary has Parkinson’s, Updike’s overall image of 65-year-olds in 1969 is of people who really are over the hill. (“Living so long in this day and age?” Really?) Or as they used to say of St. Petersburg, they were in “God’s Waiting Room” (shown at left):

St. Pete became a mecca for retired people. They flocked to the sunshine and lived in the many residential hotels in the downtown area. The symbol of St. Pete became old people sitting on the many green benches that dotted the sidewalks of the city.

But just like 40-cent beer you could buy in 1969 (plus a dime for the tip), those days are long gone. See for example “60 is the new 30,” and also “Why 60 Is The New 30.” The latter post noted that the “55-64 age group has shown the largest increase in entrepreneurial ventures, now accounting for more than 20 percent of all start-ups.” (Thus literally “starting over when our grandparents would be strolling around golf communities in Florida.”)

I should note that there is some debate on whether 60 is the new 30, or the new 40. See Is 60 the New 40? – which noted that what elderly “meant to the Greatest Generation doesn’t hold for their offspring, the baby boomers.” There’s also 60, Not 50, Is The New Middle Age – Huffington Post, and New research shows 60 is the new 40 – KING5:

Increasingly, people over 60 feel more like 40, and now they have the science to back them up… The new research argues that since life expectancy continues to rise, age 60 should not be considered old. It’s more “middle age,” because for many, there’s a lot of living left to do after age 60, even embarking on second or third careers.

Or as you might say of the Christie Brinkley image below: “Now that’s turning 60!”

A good argument for “60 is the new 30…”

A good argument for “60 is the new 30…”

The upper image is courtesy of blog.modernmechanix.com/issue/?pubname=SaturdayEveningPost.

The Churchill image is courtesy of Winston Churchill – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

The Armstrong-on-the-moon photo is courtesy of 1969 – Wikipedia.

The lower image is courtesy of People magazine, www.people.com/people/article/0,,20780764,00.html.