“Sperm Whales – The Chase…”

I first read about the Essex 54 years ago. (I was 10 or so.)

I first read about the Essex 54 years ago. (I was 10 or so.)

My aunt gave me a set of American Heritage Junior Books. The one I liked best was The Story of Yankee Whaling. (Published in 1959.)

But that book didn’t just include the story of the Wreck of the Essex. (With a POW – loosely translated as “angry whale” – ramming and sinking a ship, as shown in Ron Howard’s new In the Heart of the Sea.)

Yankee Whaling also included the gory tale of Samuel Comstock, star of the “bloodiest mutiny in the history of American whaling,” on the whale-ship Globe:

The mutineers [in 1815] killed Captain Worth and three other officers. Soon after William Humphries, one of the mutineers, was accused of plotting to take the ship; a kangaroo court of the mutineers tried him and, finding him guilty, hanged him.

Yankee Whaling had vivid descriptions of the mutineers hacking up some victims – mostly officers – and throwing others to the sharks. (Just the stuff 10-year-old boys love to read.)

Which could mean the Globe mutiny will soon be “coming to a theater near you.” In the meantime we have Heart of the Sea. That movie shows a whale sinking a ship, then “stalking” the survivors 2,000 miles across the vast Pacific. (In a bit of Hollywood hyperbole.)

On the other hand – in 90 days at sea, in small leaky boats and without enough food or water – the eight survivors of the Essex did things that the Globe mutineers would likely have found revolting. (See the classic joke, re: “the peasants are revolting.”)

On the other hand – in 90 days at sea, in small leaky boats and without enough food or water – the eight survivors of the Essex did things that the Globe mutineers would likely have found revolting. (See the classic joke, re: “the peasants are revolting.”)

There’s more on that later, but first note Garry Wills‘ version of the Lord’s prayer. His version reads, “and bring us not to the Breaking Point.” (Instead of the usual “lead us not into temptation.”)

Briefly, Heart of the Sea tells the story of eight men – survivors of the original crew of 21 – who got forcibly taken to their breaking point, then well beyond that.

Which is another way of saying the original – true – story was bad enough.

The problem? The true story of eight men surviving 90 days of living hell – on the vast Pacific – is both incredibly long and incredibly boring. (On film anyway.) Which is another way of saying that amount of living hell doesn’t translate well to film. So in making the movie, Howard had to take liberties with some facts and make up others out of whole cloth.

Despite all that, the film earned my highest compliment. I paid three times more than usual – to see the IMAX version – and still felt like I got my money’s worth.

Getting back to the Essex: I read the American Heritage version 50 years ago. Then five or six years ago I came across the book version of Heart of the Sea, by Daniel Philbrick.

The heart of the story – what made Philbrick’s book different – was that tale of eight men in small boats, undergoing 90 days of heat, hunger and thirst. And the book version gave that long, boring ordeal its full scope. But a film is like a shark. It has to move – visibly – or it will “die.” (Lose its audience. Or to paraphrase McLuhan, “the format shapes the message.”)

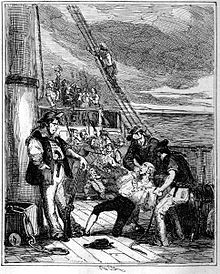

Accordingly, in making a film of Heart of the Sea, Ron Howard came up with a workable yet eminently appealing mix of fact and fiction. For starters, he used the classic seafaring style, focusing on “two quarrelling men in charge of a big ship, like Mutiny on the Bounty” – as shown at left – “or Jaws.” (See “scurvy and beards.”)

Accordingly, in making a film of Heart of the Sea, Ron Howard came up with a workable yet eminently appealing mix of fact and fiction. For starters, he used the classic seafaring style, focusing on “two quarrelling men in charge of a big ship, like Mutiny on the Bounty” – as shown at left – “or Jaws.” (See “scurvy and beards.”)

Another twist was the flashback: One remaining survivor – Thomas Nickerson – interviewed by Herman Melville (“Moby Dick“) some 30 years after Nickerson served as cabin boy on the Essex.

And “young cabin boys” raise an historical anomaly:

In 1822 … New England mothers sent their sons to kill whales in the Pacific Ocean at an age when modern parents would think twice about letting them have the car for a weekend.

Which brings up an early departure of fact in the film. Melville actually interviewed Pollard, long after he’d lost his “captaincy.” Some three years after the Essex sank, Pollard commanded the whale-ship Two Brothers when it sank. (Off the Frigate Shoals.) So by the time he got interviewed by Melville, Pollard had been demoted to “night-watchman” on Nantucket Island. (And as such considered a “nobody” to the islanders.)

And speaking of anomalies: The film showed First Mate Owen Chase as the real hero. It also showed Pollard as both a man who owed his captaincy to nepotism – connections – and a lesser sailor than Chase. But once the ramming happened, Pollard recommended a shorter course to a closer set of islands. (A course that would take advantage of prevailing “tail winds.”)

But unlike the cliche “Captain Bligh,” Pollard let himself be persuaded by Chase. So the three small boats set sail for South America – 2,000 miles away – against the prevailing winds. But as Wikipedia noted: “Herman Melville later speculated that all would have survived had they followed Captain Pollard’s recommendation and sailed west.”

(It seems Chase and the crew feared the closer islands – the Marquesas – were inhabited by cannibals. Which seems highly ironic, given what actually happened later...)

In yet another departure from fact, the real whale didn’t stalk the boats 2,000 miles across the Pacific. Nor did the whale “have a moment” with Chase, near the end of 90 days adrift. (When Chase refused to harpoon the whale-stalker, despite Pollard’s goading to do so.)

The film did feature an accurate translation of a “Nantucket sleighride“,” as seen at right. It also showed a “flurry:” The dying whale spraying his tormentors with a mixture of blood from his pierced lungs, along with mucus and seawater. (In some manner of Freudian anointing.)

Then there were the “chockpins” worn by experienced whalers. What the film didn’t show: They were apparently worn to “get babes.”

Then there was the matter of the boats landing on Henderson Island. (Not Ducie Island, as in the film.) Years after the wreck three skeletons were found on Ducie Island. They were believed to be from the lost third-of-three boats “never to be seen again,” but that was never confirmed.

And finally, the film ended with two popular tropes. One was that of corrupt businessmen, in the form of a “board of inquiry.” The money-grubbing businessmen on the Nantucket board were shown arm-twisting Chase and Pollard to say the Essex ran aground, and that the missing crew-members drowned. (They were afraid of higher insurance rates.)

A “board of inquiry” that apparently never took place, or at least not in that way.

The other was the look into the future trope. The film ended with Nickerson and Melville parting ways after the all-night session of drinking, recalling and writing. Nickerson told Melville – with faint disbelief – of a “new” discovery of oil, in the ground, somewhere in Pennsylvania…

Which led to the cartoon “whale celebration” below..

* * * *

All in all, Heart of the Sea is a film well worth seeing. For those who’d love to get a feel for the pure adventure, “such as befell early and heroic voyagers…” And especially for those who’d love to get a feel for being “alone, alone, all all alone, alone on the wide, wide sea…”

* * * *

Whales “celebrating the discovery” of oil in Pennsylvania…

* * * *

The upper image is courtesy of Artifact Article: Sperm Whaling: The Chase:

Three whale ships can be seen in the background, while two whaleboats are in the foreground. In the whaleboats, boatsteerers are seen with their harpoons raised. As they chase the whale, one can image that the call “thar She blows!” was sounded, as several whales can be seen spouting as they surface.

The illustration was by Benjamin Russell, born into a family of whaling merchants. He started work in the office of a whaling agent in New Bedford, MA, but “showed more aptitude for drawing than business, often to the displeasure of his superiors.” He later spent four years on the whale ship Kutusoff. There his “acute observational sensitivity” resulted in sketches with “impeccable detail… Russell’s images were rendered with mastered accuracy rather than artistic intention.”

See also Benjamin Russell: Whaleman-Artist, Entrepreneur | New Bedford.

For more on the sources used in this post, see the notes below.

The “Story of Yankee Whaling” image is courtesy of American Heritage Junior Library | Series | LibraryThing. See also American Heritage Junior Library | eBay, where the book is available individually for $1.95, or as part of a set of seven, for $21.00. For more on the author, see below.

Re: Samuel Comstock. See also Globe (1815 whaleship) – Wikipedia, and Helter-Skelter on the High Seas – NYTimes.com. The latter was a review of two books said to “unravel the saga of the bloodiest mutiny in the history of American whaling.” Comstock was said to be “a keen ladies’ man,” to wit: He possessed a “superabundance of something which the fair sex seemed to consider a very agreeable substitute.” (For affection.) Also this note, as previously noted:

In 1822 … New England mothers sent their sons to kill whales in the Pacific Ocean at an age when modern parents would think twice about letting them have the car for a weekend.

Re: “coming to a theater near you.” See also In a World – TV Tropes.

Re: “Your majesty, the peasants are revolting!” “They certainly are!” See also Count de Money / “The People Are Revolting” – YouTube, and/or Ambiguity – Simple English Wikipedia, which noted the “British comedian Ronnie Barker said that he loved the English language because there are so many jokes you can make using ambiguity.”

Re: “breaking point.” See Garry Wills’ What the Gospels Meant, Viking Press (2008), at page 87; found in Part II, “Matthew,” Chapter 5, “Sermon on the Mount:”

Our Father of the heavens, your title be honored … and bring us not to the Breaking Point, but wrest us from the Evil One.

The usual translation in the Lord’s Prayer is – as noted – “And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil.” See Wikipedia. My life experience tells me the term “breaking point” is more accurate and appropriate. See also The True Test of Faith, in my other blog.

The “whale’s eye” image is courtesy of In the Heart of the Sea (film) – Wikipedia. See also In the Heart of the Sea (book) – Wikipedia, which included this on the author’s sources:

Philbrick utilizes an account written by Thomas Nickerson, who was a teenage cabin boy on board the Essex and wrote about the experience in his old age; his account was lost until 1960 but was not authenticated until 1980 before being published, abridged, in 1984. The book also utilizes the better known account of Owen Chase, the ship’s first mate, which was published soon after the ordeal.

Re: Marshall McLuhan and “the format shapes the message.” The Rotten Tomatoes review said the “admirably old-fashioned” film-story boasted “thoughtful storytelling to match its visual panache, even if it can’t claim the depth or epic sweep to which it so clearly aspires.” My theory is that neither the depth nor epic sweep of the true story could have been adequately translated to film.

The “Bounty” image is courtesy of Mutiny on the Bounty – Wikipedia. The caption: “Fletcher Christian and the mutineers seize HMS Bounty on 28 April 1789. Engraving by Hablot Knight Browne, 1841.”

Re: The “whale-stalking.” Wikipedia said that after ramming the Essex – twice – the whale “finally disengaged its head from the shattered timbers and swam off, never to be seen again.”

Re: “have a moment.” An allusion to the 1984 film, Moscow on the Hudson (1984):

Vladimir Ivanoff: [confronting a stranger following him down the street] FBI? Gay Man on Street: FBI? No. Vladimir Ivanoff: KGB? Gay Man on Street: No. G-A-Y. Vladimir Ivanoff: Gay? Oh, no, no. Gay Man on Street: Sorry. You have a nice face. I thought we had a “moment” back there.

The “Nantucket sleigh ride” image is courtesy of jrusselljinishiangallery.com/pages/sticker-pages.

Re: the number of survivors and their length of time at sea. It took 90 days for the Owen Chase boat to be rescued, with three survivors. It took 95 days for the Pollard boat to be rescued, at a different location, with two survivors. The three original boats were separated in a storm, and the boat headed by Obed Hendricks – “boatsteerer” – was never seen again. Wikipedia: “A whaleboat was later found washed up on Ducie Island, just east of Henderson Island, with the skeletons of three people inside… [S]uspected to be Obed Hendricks’ missing boat, the remains were never positively identified.” Thus the eight survivors, including the three who stayed on Henderson Island.

Re: “Look into the future” trope. It’s actually known as Externally Validated Prophecy: “When a character makes a prediction about the future which is not fulfilled in the work, yet an audience aware of history knows will be fulfilled.”

Re: “pure dispassionate adventure.” The quote is from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes. See also Donkey travel – and sluts and “Pity the fool” from my other blog.

The lower image is courtesy of Sperm whaling – Wikipedia, including the caption: “An 1861 cartoon showing sperm whales celebrating the discovery of new petroleum wells in Pennsylvania. The proliferation of mineral oils reduced demand for their species’ oil.” The caption in the cartoon itself: “Grand ball given by the whales in honor of the discovery of the oil wells in Pennsylvania.”

* * * *

Sources used for this post – or worth more reading: Heart of the Sea (film) – Wikipedia, Essex (whaleship) – Wikipedia, History of whaling – Wikipedia, Girl on a Whaleship – Images, Essex explained, and a review: “Heart of the Sea” – Apollo 13 with scurvy and beards:

There was rumored to exist a secret society of young women on the island whose members vowed to wed only men who had already killed a whale. To help these young women identify them as hunters, boatsteerers wore chockpins (small oak pins used to secure the harpoon line in the bow groove of a whaleboat) on their lapels.

See The Real Story Behind “In the Heart of the Sea,” which also included this:

The harpoon did not kill the whale. It was the equivalent of a fishhook. After letting the whale exhaust itself, the men began to haul themselves, inch by inch, to within stabbing distance of the whale. Taking up the 12-foot-long killing lance, the man at the bow probed for a group of coiled arteries near the whale’s lungs with a violent churning motion. When the lance finally plunged into its target, the whale would begin to choke on its own blood, its spout transformed into a 15-foot geyser of gore that prompted the men to shout, “Chimney’s afire!” As the blood rained down on them, they took up the oars and backed furiously away, then paused to observe as the whale went into what was known as its “flurry.”

The site also noted that Melville interviewed Captain Pollard for his later book, Moby Dick, not Nickerson. After a second failed whaling voyage, Pollard became the town’s night watchman; “To the islanders he was a nobody…” For a lengthy account and history see the New York Times review.

A final note: The American Heritage Yankee Whaling was written by Irwin Shapiro (1911–1981), an “American writer and translator of over 40 books, mostly for children and about Americana:”

After an initial foray into writing radical literature that encompassed his last year as a communist, Shapiro turned to children’s books… He published many titles for Golden Books[, including one thought to be] a coded message about the imprisonment of American spy Isaiah Oggins in the GULAG… The Library of Congress holds 44 titles in his name.

See Wikipedia, and also Irony … Literary Devices.