Declaration of Independence: John Adams – “patched and piebald” – stands at center, hand on hip…

Declaration of Independence: John Adams – “patched and piebald” – stands at center, hand on hip…

Here’s a break in the action from my multi-volume Mid-summer Travelog.

I recently got some much-needed cheering up on the political front. I got cheered up by listening to two lectures on CD. The one I just started is Brotherhood of the Revolution: How America’s Founders Forged a New Nation. I started listening just a few days ago.

The other CD – actually an audiobook – was Chris Matthew’s Life’s a Campaign. I talked about it on June 12, in “Great politicians sell hope.” I noted the book gave me the sense that the most of the U.S. presidents of the past have been – overall, generally, and even the ones I didn’t like – “decent, honorable and capable.” What’s more, the book gave me a sense that the same applies – in general – “to politicians today. (Gasp!)”

I’ll write more on Campaign later, but for now I’ll focus on Brotherhood of the Revolution.

I got as far as Lecture 3 – Disc 2, Track 6 – where I felt moved to note the disconnect between history as it’s written – and taught – and as it actually happens. (How it’s actually lived through.) John Adams – for one – preferred the more-accurate history as actually lived through, as opposed to the popular rose-colored glasses. See Adams and American Mythology:

In elementary school, they told us that the Founding Fathers were Great Men. They sat down in Philadelphia in 1776 with a mandate from God, and calmly and certainly wrote the Declaration of Independence. Then they fought the British, and then they founded the first democracy ever, and then independence and democracy spread to the rest of the world. They knew what they were doing. They were carried by a sure and steady tide.

The American Mythology site said this mythos “became popular while Adams was still alive,” but it was a view of history he loathed. That was followed by a statement of “nothing certain in what those ‘great men’ did in Philadelphia.” Our American History – as lived through – was “improvised, patched together, made up from one moment to the next, with every outcome uncertain until it was safely past.”

The site noted the musical 1776 – and film, shown at left – which had John Adams saying these words. (Words that mirrored “almost exactly” what he wrote in a letter to Benjamin Rush in 1790):

The site noted the musical 1776 – and film, shown at left – which had John Adams saying these words. (Words that mirrored “almost exactly” what he wrote in a letter to Benjamin Rush in 1790):

I’ll not be in the history books. Only Franklin. Franklin did this, and Franklin did that, and Franklin did some other damn thing. Franklin smote the ground, and out sprang General Washington, fully grown and on his horse. Then Franklin electrified him with that miraculous lightning-rod of his, and the three of them – Franklin, Washington, and the horse – conducted the entire War for Independence all by themselves.

The article noted another book by Ellis, his 2002 Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation. See also Wikipedia, which described the “fractious disputes and hysterical rhetoric of these contentious nation-builders.” (Emphasis added.)

Wikipedia said these disputes might come across today as “hyperbolic pettiness.” (Hyperbole is the use of “exaggeration as a rhetorical device.”) But the article added that Founding Brothers showed the real issues, the “driving assumptions and riveting fears that animated Americans’ first encounter with the organized ideologies and interests we call parties.” (And apparently that “hysterical rhetoric” isn’t limited to our times.) Then came Adams:

As Adams remembered it… ‘all the great critical questions about men and measure from 1774 to 1778’ were desperately contested and highly problematic… Nothing was clear, inevitable, or even comprehensible to the soldiers in the field at Saratoga or the statesmen in the corridors at Philadelphia: ‘It was patched and piebald policy then, as it is now, ever was, and ever will be, world without end.’ The real drama of the American Revolution … was its inherent messiness.

And incidentally, the term “piebald” usually refers to the spotting on a certain type of horse. (As shown at right.) But in a metaphoric sense it means “composed of incongruous parts.” See for example piebald – Wikipedia, and Piebald … Merriam-Webster.

See also American Creation – Book Review, noting Ellis on Adams’ theory that – in the history of the Revolution as people lived it – “contingency played a large role in shaping the decisions of leaders who were often making it up as they went along, teetering on the edge of the abyss.”

Note that term too, “teetering on the edge of the abyss,” which also seems to apply today.

Which brings us back to Brotherhood of the Revolution. As noted, I’ve gotten as far as Lecture Three. Ellis said that in the process of studying Adams – living through the Revolution as he did – it was most fascinating to read his letters and diaries. Those papers give “a sense of how confused and how incoherent and inchoate events seemed at the time.” And this was especially true of the letters of Adams to his wife Abigail in the critical years 1775-1776.

Ellis noted the turmoil of those two years, engulfing the Colonies. But during that key time in American History, John and Abigail wrote mostly about their children, and about the smallpox epidemic raging through America at the time. See Siege of Boston – Wikipedia. Their biggest fear was of losing their children. (And so it likely is of all history “as it’s lived through.”)

Which Ellis said brought up the point that when we study history, we normally divide it into “segments.” But history as it’s lived through – as it happens – “happens in a variety of different ways, all at the same time.” Which brings up that key difference, between how Adams saw such developing history, and how a guy named Thomas Jefferson saw it.

In later years, Jefferson recalled the Revolution as “clear moral conflict between right and wrong.” But Adams saw the Revolution as a chaotic event, a “concatenation, a tumbling, overlapping experience of turmoil.” And that chaos – illustrated at left – swept up all Americans living at the time. Adams rejected Jefferson’s view of American history. He thought his patched and piebald memory of the war was more accurate:

In later years, Jefferson recalled the Revolution as “clear moral conflict between right and wrong.” But Adams saw the Revolution as a chaotic event, a “concatenation, a tumbling, overlapping experience of turmoil.” And that chaos – illustrated at left – swept up all Americans living at the time. Adams rejected Jefferson’s view of American history. He thought his patched and piebald memory of the war was more accurate:

“We didn’t know what we were doing. We were improvising … always on the edge of catastrophe.”

Which brings us to today’s political gridlock.

Before I listened to Brotherhood, I felt that we too are living in a time of chaos. See Gridlock in Congress? It’s probably even worse than you think (Washington Post), Political gridlock: Unprecedentedly dysfunctional, (The Economist), and Political Gridlock – Huffington Post. (A list of articles on the current gridlock.)

But after listening to the CD, I came to think maybe today’s gridlock is more of a “Situation Normal.” (Or as Adams would say, politics “as it is now, ever was, and ever will be, world without end.”) Remember those terms, “improvised, patched together, made up from one moment to the next?” “Hysterical rhetoric?” “Teetering on the edge of the abyss?”

As Churchill said, “No one pretends democracy is perfect or all wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others that have been tried…”

So cheer up. At least we haven’t come to this! (Not yet anyway…)

Congressman Brooks makes a point of order with Senator Sumner…

The upper image is courtesy of Wikipedia.org/wiki/Declaration_of_Independence_(Trumbull). The caption: “50 men, most of them seated, are in a large meeting room. Most are focused on the five men standing in the center of the room. The tallest of the five is laying a document on a table.”

See also The Declaration of Independence by John Trumbull, and John Adams – Wikipedia, with the caption: “Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence depicts committee presenting draft Declaration of Independence to Congress. Adams at center has hand on hip.” Thus Trumbull showed “only” the presentation of the first draft of the Declaration, not the signing itself.

Re: The views of Ellis – and Adams – on history as people actually live through it: “What in retrospect has the look of a foreordained unfolding of God’s will was in reality an improvisational affair in which sheer chance” – not to mention pure luck – “determined the outcome.” See also Trust and Caution – The New York Times, which noted: “How to live in a tragic milieu and yet strive toward triumph … was a consuming concern for the founders.” As it is even to this day…

Re: 1775-1776. The full cite in the text is American Revolution: Conflict and Revolution 1775-1776.

Re: Smallpox during the siege of Boston. See The Siege of Boston & Smallpox – 1775 – 1776, and Colonial Germ Warfare : The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. The latter especially noted the circumstantial evidence that the British engaged in a form of germ warfare against Americans during the siege. The article noted most British troops had either been inoculated or had smallpox, and thus were immune. Further, smallpox was endemic in Europe at the time – “almost always present” – so that nearly everyone had been exposed, and “most of the adult population had antibodies that protected it.” On the other hand, most American soldiers were susceptible; at the time of the siege most Americans had never come in contact with the virus, and thus had no immunity.

As Ellis also noted in Brotherhood of the Revolution, John Adams was a paradox, a “conservative revolutionary,” as shown by his defending the British soldiers after the “Boston Massacre.” See The Boston Massacre Trials | John Adams Historical Society, and also Boston Massacre – Wikipedia:

The trial of the eight soldiers opened on November 27, 1770. Adams told the jury to look beyond the fact the soldiers were British. He argued that if the soldiers were endangered by the mob, which he called “a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes, and molattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tarrs [i.e. sailors],” they had the legal right to fight back, and so were innocent. If they were provoked but not endangered, he argued, they were at most guilty of manslaughter.

Which raises the question: Are there any such conservative revolutionaries today?

The chaos image is courtesy of Chaos theory – Wikipedia. The caption:

Turbulence in the tip vortex from an airplane wing. Studies of the critical point beyond which a system creates turbulence were important for chaos theory[, including] that fluid turbulence could develop through a strange attractor, a main concept of chaos theory.

The Churchill quote is from Winston Churchill’s Quote on Democracy : Papers – Free Essays.

The lower image is courtesy of Caning of Charles Sumner – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. The caption: “Lithograph of Preston Brooks‘ 1856 attack on Sumner; the artist depicts the faceless assailant bludgeoning the learned martyr.” See also 1851: Caning of Senator Charles Sumner – May 22, 1856 (Senate Archives), and Preston Brooks – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Note that Sumner recovered from the attack and returned to the Senate in 1859. He served throughout the Civil War and beyond, until 1872, where he served much of the time as “powerful chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.”

Brooks on the other hand died less than a year later, “unexpectedly from croup in January 1857… The official telegram announcing his death stated ‘He died a horrid death, and suffered intensely.'”

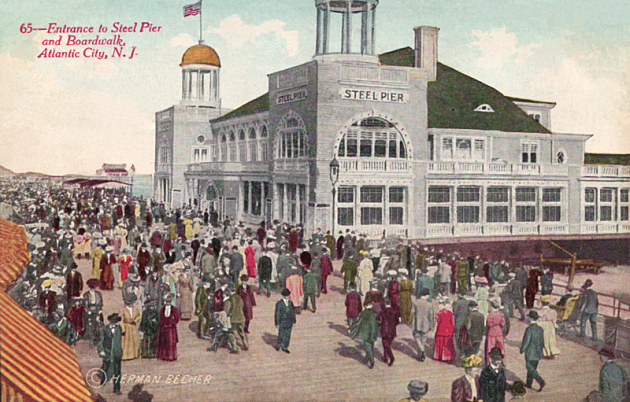

Like kayaking across the Delaware River just below Wilmington (at left), or seeing Atlantic City from the 32d-floor penthouse of a swanky hotel, or hiking 17 miles in a day and a half on New york City’s hard concrete sidewalks.But more about that later.

Like kayaking across the Delaware River just below Wilmington (at left), or seeing Atlantic City from the 32d-floor penthouse of a swanky hotel, or hiking 17 miles in a day and a half on New york City’s hard concrete sidewalks.But more about that later. I figured to save some money on the way up to

I figured to save some money on the way up to

Eventually I took the

Eventually I took the

I did need to stop at local libraries, to use their computers. But only if I needed a secure connection, to check my bank accounts or – with the Ford being new – to make the first payment a few days into the trip. (At the

I did need to stop at local libraries, to use their computers. But only if I needed a secure connection, to check my bank accounts or – with the Ford being new – to make the first payment a few days into the trip. (At the